The Feast of St. Patrick: Not about Parades and Green Beer

by Katie Cook

by Katie Cook

I grew up in Shamrock, a small town in the Texas Panhandle founded by Irish Catholics who settled in dugouts along the north fork of the Red River in the late 19th century. Over the decades, the town migrated south a couple of miles to string out along US Route 66, which later became Interstate 40. By then, the population was dominated by Protestants who were not Irish, but the beautiful St. Patrick Catholic Church on Main Street stands as a memorial to the town’s founders.

Another memorial that remains to this day is one of the most famous St. Patrick’s Day festivals in the country—especially when you consider there have never been more than 4,000 residents in Shamrock. When I was growing up, it was as big as Christmas. At one time, 20,000 people attended. The festivities have included a banquet with celebrity speakers, an impressive parade, the Miss Irish Rose beauty pageant, a high-school band contest, an old fiddlers’ reunion and a carnival. There was no green beer, which is ubiquitous across the US on March 17, because our county was dry.

After Christmas every year, men in Shamrock had to purchase special permits if they planned to shave, because they were supposed to grow beards for the Donegal Beard contest on St. Patrick’s Day. The city flew in fresh shamrocks from Ireland for the festival. The newspaper for that week was printed on green paper, contained greetings from every merchant and organization in the region and was 10 times as big as usual. I could go on, but I think you’re getting the idea.

That festival was, and probably still is, largely organized and attended by people who have little or no idea who St. Patrick was. I lived the first 18 years of my life in Shamrock and eagerly anticipated his feast day without knowing what a feast day was. I didn’t give the man a second thought until I got to college. It was then that I discovered that the Feast of St. Patrick was not really about parades and green beer.

There is an incredible amount of scholarship on the man who called himself Patricius. Unfortunately, the vast majority of it consists of disagreements. We don’t know for sure when he was born or when he died. Before I give you the generally accepted story, please bear in mind that every detail has been debated at length.

Modern scholars generally accept the story that he was born and named Maewyn Succat in 387 CE in Roman Britain. His father was Calpernius, who seems to have been a civic and religious leader. His mother’s name was Conchessa.

At the age of 16, according his own writings, he was abducted and taken to Ireland, where he served for six years as a slave. His job was to tend sheep. Since he came from what seems to have been an upper-class family, he was educated and intellectually inquisitive. He learned a great deal about the Irish language and culture. He also wrote that he had been an unbeliever in his parents’ household in Britain, but was converted to Christianity during his captivity in Ireland.

Apparently, the young man experienced a vision that helped him escape from Ireland, but he was captured again on his way to Britain and stayed for two months in France. There he became interested in French monasticism. (Make a note of that. It’s important.) Then he apparently had another vision, this time of an Irish person asking him to come and teach the Irish about Christianity. He returned to Ireland and started 300 churches and a number of monastic houses. Also, according his own writings, he baptized more than 100,000 people.

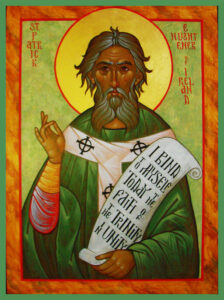

Patrick, or Pádraig in Gaelic, is the primary patron saint of Ireland, even though he was never officially canonized by a pope. He is also venerated in the Orthodox Church, in the Anglican Communion and in the Lutheran denominations. Historians generally believe that he was active as a missionary in Ireland in the fifth century. Most of the material that comes to us today comes from the seventh century. Primary corroborative sources are scarce.

Patrick’s feast day was set on March 17, because tradition has it that he died on that day, although the sources for that are—you guessed it—obscure. One legend says that he used a shamrock as a visual aid in explaining the doctrine of the Trinity to the Irish people. Another legend says that he drove all of the snakes out of Ireland. (The truth is, according to Irish natural scientists, there never had been any snakes in Ireland.) A third story says that he always carried an ash wood walking stick and stuck it in the ground while he was preaching, and at one place it took so long to get the people to understand that the stick had taken root by the time he was finished. That place is known as Aspatria, or the ash of Patrick.

Patrick apparently encountered opposition from just about everybody. Much of his writing consists of defending himself against all kinds of accusations. However, one enduring writing that is attributed to him is Saint Patrick’s Breastplate, which has been translated and distributed in a number of versions. It was described by one priest as “a whale of a prayer.” Click here to read my favorite version.

Tradition says that Patrick died in 461 CE in what is now known as Downpatrick and was buried in the Down Cathedral churchyard there. No matter which of the stories are true or which ones may have been enhanced, it is certain that he had a profound effect on the religious face of Ireland and its people.

Katie Cook is the Seeds of Hope editor. Click here for a pdf of this story.